How does the ear maintain its spectacular performance despite age, trauma and environmental challenge?

This website serves as a hub for the scientific work of Eric Le Page, Ph.D, aiming to provide an overview of the regulation of cochlear performance and add new hypotheses.

Received 2 July 2025 and AI review of the paper listed as Direct testing of the biasing effect of manipulations of endolymphatic pressure on cochlear mechanical function

The review seems balanced, in line with objectives of the project in France, but issues several reservations, like a couple of projects mentioned below have been interrupted before completion so that the report is at the level reached at the scientific meeting at which it was presented.

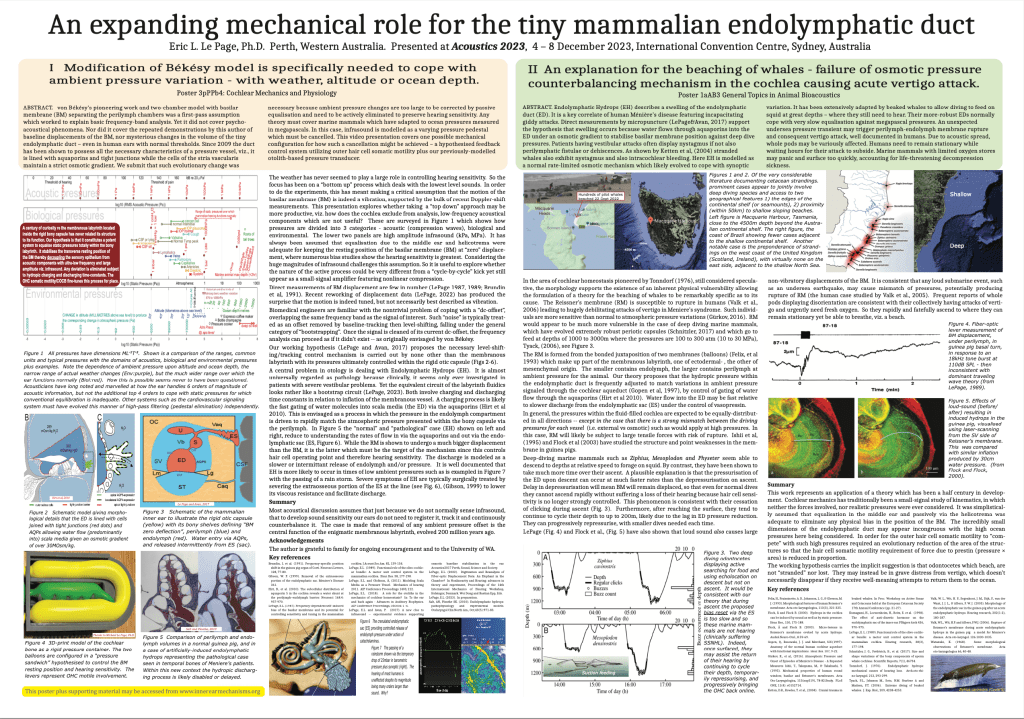

Poster presentation to the combined meeting of the Acoustical Society of America and the Australian Acoustical Society 2023 held at the International Convention Centre, Sydney Australia, 4-8 December, 2023.

full resolution here

Readers may appreciate some extended discussion on the purpose of the site as well as information about the book entitled “The Mechanics of Cochlear Homeostasis” and some more thoughts on specific topics of interest.

Author’s potted summary of Cochlear Mechanics for last 70 years

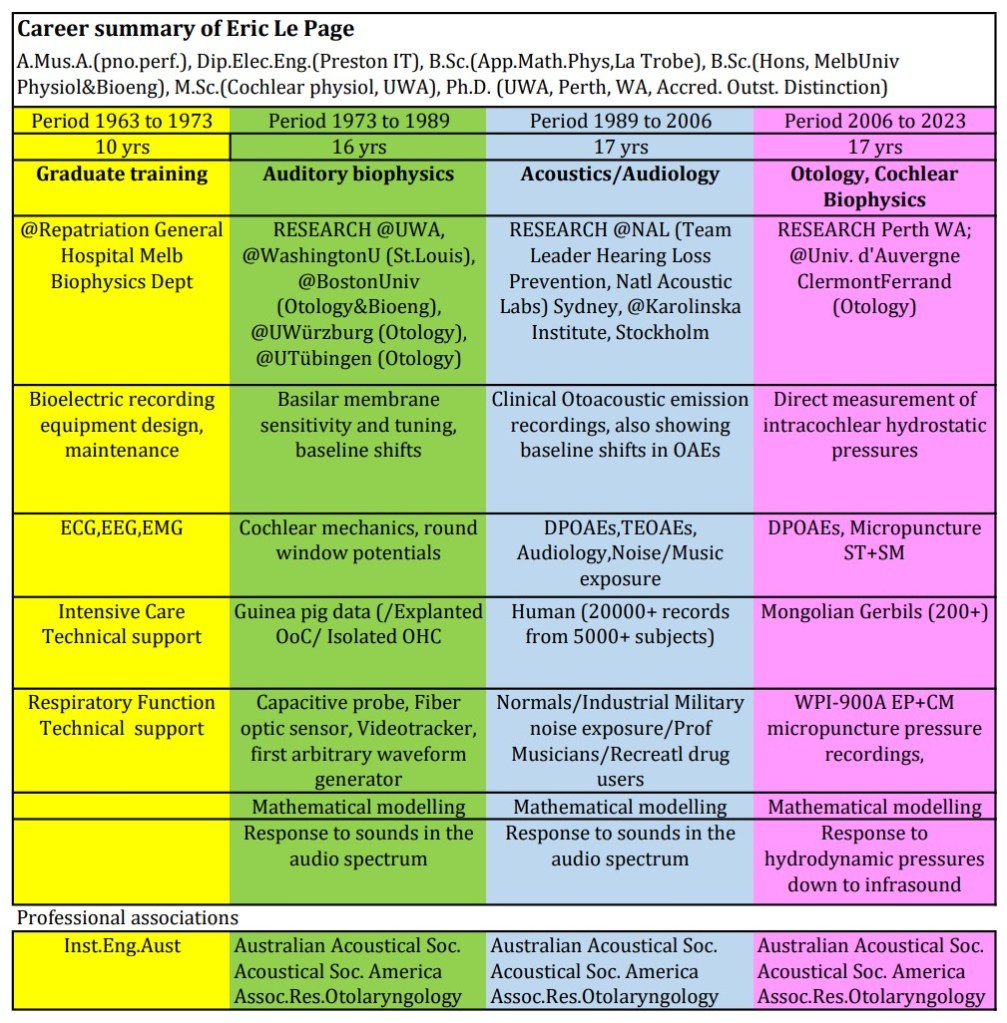

Hungarian telephone engineer Georg von Bekesy set out to understand how the microanatomy of the mammalian cochlea accounts for its extraordinary performance analysing sound, particularly its high sensitivity, which is lost in old age. He needed to make measurements of vibrations of the basilar membrane (BM) in guinea pigs due to incoming sound. He had to use very loud sounds. It was concluded that at threshold sound levels these vibrations must be vanishingly small. So, in Australia, in the 1960s, physicist Brian Johnstone developed a velocity-based technique which was sensitive enough. In 1971 Wisconsin student William Rhode, used this same technique but importantly found the vibration was nonlinear with sound level.

In 1973 Melbourne hospital biomedical engineer/musician Eric Le Page joined Johnstone’s group in Perth. He was assigned a highly technical project — for which he determined could not be achieved using Johnstone’s technique. Instead, he developed a displacement-based technique – a capacitive probe. It succeeded with the objective and provided qualitative support for Rhode’s data. Within months, however, it was clear that Bekesy’s approach had neglected the possibility that the BM motion could not be completely described as a vibration — the resting position of the BM was changing hugely, compared with the size of the expected vibration.

Prof. Flock’s group at the Karolinska showed similar baseline shifts, these data were again strongly rejected. The only investigator who showed awareness of the possibilities that the baseline shifts meant a system of controlling sensitivity was H.P. Zenner.

The field adopted the position that a Nobel prize winner cannot be wrong; all the reports of baseline shifts must be a product of artifact, poor experimentation, or simply experimental damage. Sharp neural tuning did not survive invasion of the periotic bone. Nobody allowed for the fact that the loss in tuning might be simply due to a loss of baseline regulation – a low-frequency bias affecting hearing sensitivity. The preservation of the compressive nonlinearity was considered irrelevant.

LePage switched tack. Instead of only relying upon descriptions of cochlear kinematics (descriptions of motions without forces), it was necessary to measure forces driving the basilar membrane motion. The most readily testable approach is to measure pressures within the membranous labyrinth from which the actual forces could be estimated. LePage requested to join the group in Clermont-Ferrand where they were monitoring changes in distortion product (DP) levels from patients lying on a tilt table, while the angle of tilt was varied over a right angle. Highly reproducible changes in DP phase provided an indirect method to monitor the effects of atmospheric pressure change estimated from the angle of tilt. LePage needed to measure intracochlear pressures in living laboratory animals. A WPI-900A micropuncture system was borrowed from The Netherlands. It should have revealed any significant pressures in the cochlea, but dozens of papers using the technique didn’t show any pressures of significance. It seemed likely that a key factor was missing in the design of experiments using the WPI-900A servo system.

On his third self-funded visit to France LePage determined a likely reason for the poor progress with the servo-controlled system. As will be shown, the mammalian cochlea is unlike any system to which the WPI-900A had previously been applied, including intra-ocular pressure measurements, kidney tubules and the roots of trees: The mammalian cochlea is itself behaving like a servo-control system. It was itself reacting to (fighting) the control pressures being injected by the WPI-900A. With that realisation, the experimental setup could be better understood. Data showing intracochlear pressures of fractions of one atmosphere were then readily produced and they were modified by triggering the aquaporin (water channels) into action.

Reading the cochlear mechanics literature, no publication has been found to consider the possibility that the mammalian cochlea may have evolved so as to cope with continuous, second-to-second variations in atmospheric pressure — viz. the weather. Compensation for synoptic variation has always been treated as automatic, or maybe due to the combined actions of passive equalisation due to the middle ear and helicotrema.

However, in 2009 the Löwenheim group provided a monumental clue. They showed the tiny vessel contains the essential components of an osmotic mechanism which accounts for the baseline shifts, viz.: the endolymphatic duct is lined with aquaporins and with tight junctions. Given the ionic species across the stria membrane, water would flow through the any aquaporins gated open, and the osmotic pressure required to arrest the flow could be up to 7 atmospheres. This fortified the hypothesis that the endolymphatic duct functions to counterbalance quasi-static variations in ambient pressure.

Since 2011 LePage (MoH2011) has been exploring the hypothesis that scala media (part of the endolymphatic duct) is actually a pressure vessel. It is so tiny nobody studying the processing of sound has ever suspected it.

In 2017 at the Australian Acoustical Society meeting in Perth, LePage presented anatomical, theoretical and experimental support from his French data (“A new clue to infrasound”, available below).

By 2022 LePage had reanalysed his fiberoptic data and shown that the concept of an amplified vibration could be far removed from the best explanation (presented at MoH2022).

How all these ingredients fit together as a holistic theory may take a few years. Work in progress.

Current scientific work includes:

- INFRASOUND is that group of acoustic frequencies below the normal hearing range from roughly 20 Hz to 20,000 Hz (for humans). The ear of mammals has evolved over millions of years do deal with the fact that we live on a planet with an atmosphere with an atmospheric pressure at sea level of 14.7psi which equals 760mmHg or around 1013mbars. This level of pressure varies minute to minute by say 20mbars a day with changes in the weather. The more remarkable thing is that ambient pressure can change quite dramatically by 10 to 20 percent or more if we climb mountains, ride in aircraft (in which the cabin pressure is typically reduced to around 600 mmHg) or dive in the ocean where the pressure may be several atmospheres. Our ears have evolved to cope with such changes while continuing to hear normally — on the strict proviso that the change is very slow to allow not just the middle ear, but also the inner ears to equilibrate pressures. Aircraft take a half hour to ascend or descend, while ascents and descents in the ocean must be very slow for pressure equilibration. How the ear achieves this is detailed in a new theory supported by physiological data. This account was presented to an audience concerned with Wind Turbine Syndrome, at the Australian Acoustical Society’s meeting in Perth Australia, November 2017. The full transcript of that presentation from the Proceedings of the meeting is downloadable here. A New Clue To Infrasound – Experimental Evidence Supporting Osmotic Baseline Stabilisation In The Inner Ear.

- This means that if the magnitude of ambient pressure varies more quickly, damage can be done to the inner ear. There is a branch of otology directed at understanding the traumatic consequences of these kinds of phenomena for susceptible individuals. It would be consistent if the rate of atmospheric pressure change exceeds the normal rate of internal compensation. Such a situation appears to occur because water molecules are transported at a limited rate across the membranes via the aquaporins (specialised water channels) within the inner ear. This is a similar mechanism to controlled water transport within the kidneys. When that happens, the otoliths (see below) can receive excessive stimulation (resulting in giddiness) while more intense atmospheric pressure changes can result in membrane ruptures in the inner ear causing severe vestibular disturbances and vomiting.

- Wind Turbine Syndrome may represent susceptibility of a fraction of the population to change in atmospheric pressure, e.g. there are many reports of people who respond to particular wind patterns adjacent to mountain ranges. It would be consistent that the larger the atmospheric pressure disturbance, the more people may be affected.

- The theory tends to explain the confusion which exists with even professional investigators thinking that if some disturbance is seriously affecting the ear, then one must surely be able to hear it? If it cannot be heard, it cannot be real and claims to the contrary should be ignored! Thus the theory of cochlear homeostasis (LePage, 2006) addresses why the ear should be so strongly affected, while precise sound measurements fail to show any sound energy within the normal acoustic passband.

- Indeed this insight translates to the general area of prevention of hearing loss which addresses the much used terminology of “hearing damage”. The traditional ability to assess hearing using audiograms has long been taken to be the gold standard for assessing inner ear function but as has been shown repeatedly the technique of otoacoustic emissions gives a more direct measure of micromechanical activity in the inner ear.

- LePage MoH2017 A role for the otoliths in the mechanics of cochlear homeostasis? This was presented at the Mechanics of Hearing Workshop, Brock University, Ontario, Canada 18-24 June 2017. It is recently available in book form in AIP Conference Proceedings of the 13th Mechanics of hearing workshop: “To the ear and back again — advances in auditory biophysics” edited by Drs. Christopher Bergevin and Sunil Puria [ISBN 978-0-7354-1670-3 2018]. [Summary: For most of the history of hearing science, the cochlea and the vestibular apparatus have been regarded as essentially separate systems in the one bony capsule. By using a computational model this article illustrates the possibility of considerable functional overlap. As such it seems a good example of exaptation in which a new function has evolved by using morphology and/or mechanisms already established].

- Videos of the Lagena model to be presented at Mechanics of Hearing Workshop, Brock University, Ontario, Canada, 19-26 June 2017. The vestibular apparatus is strongly associated with sensation of balance, rotation and acceleration. The shear sensitivity of the inertial otoliths is thought responsible specifically for sensing translational movement. The video demonstrations below show that the otoliths likely have two modes, the second being sensitivity to ambient pressure. We are not normally aware of this form of stimulus except when the newly-proposed inner-ear mechanism (below) fails. This mechanism compensates for normal variations of static ambient pressure. The symptoms of failure are likely vestibular disturbance.

- The context of acoustic pressures within the bigger picture.

- All pressure (and stress) has the same dimensions (ML-1T-2), be it atmospheric air pressure, ocean pressure or sound pressure. However, the units of pressure have historically varied with the particular application e.g. atmospheres, pounds per square inch, centimeters of water, millimeters of mercury and millbars, vacuums in torr, etc. Despite the adoption of the SI unit of the Pascal, many different units continue to be used if, within any application, the numbers of those units deliver a better sense of range or precision, or are more memorable (e.g. cardiovascular or intraocular pressures in mmHg).

- Here is a one page comparison of many common ranges of pressure against the standard Pascal (Pa = 1 newton/metre2): Cross Comparison of Pressure Units – LePage2017. The three panels assist cross comparison of acoustical pressures, biological pressures and environmental pressures, with typical values shown. The point of this exercise is that mammalian hearing maintains its normal sensitivity within a close tolerance, despite ambient pressure variation 5 to 12 orders of magnitude larger than acoustic pressures. How is this achieved? It seems unrealistic to continue to presume that passive high pass filtering can cope with such a huge range and variability.

- On a sunny calm day how does atmospheric pressure vary from minute to minute, second to second? In this document are three figures:

- Fig.1) The atmospheric pressure is around 1019mbar (= 101.9 hPa), but it typically varies by ±5hPa, with on record, extreme weather variations from 870 to 1086mBar.

- Fig.2) How does atmospheric pressure vary inside an elevator ascending and descending 10 floors? Typically up to 3mbar.

- Fig.3) What is the rate of change of those elevator rides in Pa/second? Typically 20to30 Pa/s. Burswood Elevator Ride 20170527 atmospheric pressure

- The need to internally compensate for atmospheric pressure variation in the process of stabilising hearing sensitivity. The inner and outer hair cells are acutely sensitive to static position of the basilar membrane. Since ambient pressure variation is normally fairly slow, achieving this manner of equalisation between cochlear chambers can be managed with osmoregulation.

- Short video (no sound) of the first demonstration from the mathematical model, viz. showing by example how an assumed configuration for an otolith leads directly to how motion of the inertial mass is detected by the hair cells in the striola region. The calyx and dimorph cells will deliver phasic responses to the vestibular nucleus from which is derived the sense of acceleration. While physiological experiments in animals have shown this outcome, this is the first time it is explained (in the preceding reference) how it is likely achieved. The moving notch tracing out the locus represents the local kinocilia deflections within the striola region.

- LePage podium presentation for ARO_MWM2016_SanDiego 23Feb2016

- Modeling Scala Media as a Pressure Vessel

- Direct testing of the biasing effect of manipulations of endolymphatic pressure on cochlear mechanical function

- A retrospective on studies on cochlear mechanics, otoacoustic emissions and hearing loss due to overexposure – a model for dynamic mapping (Proceedings article of an invited keynote address for the Audio Engineering Society workshop, “Music induced hearing disability” held in Aalborg, end June 2015).

You can also view lists of:

Note that navigation is possible with the sidebar menu (toggle on and off by clicking the button with 3 horizontal lines, upper right hand side).

Website developed with help and insights from Michael Le Page, Ph.D. (www.mikelepage.com)